The crypto ETP space is one of the most exciting growth and innovation areas in the European ETP market. Due to the asset class being relatively nascent, however, some of the structures used do not meet the same standards as the broader and more traditional ETF and ETP markets.

Some key crypto ETP areas of concern are:

- lending arrangements

- synthetic vs physical exposure; and

- collateral structures.

Following the 2008 financial crisis, regulators imposed strict rules and transparency requirements on ETFs around these areas of concern. These are not currently being observed by many crypto ETP providers. ETC Group believes it is important that crypto ETP issuers maintain standards which are aligned with those that ETFs are subject to, as a minimum, to ensure risk management is robust and investors understand the structure and inherent risks.

Current best practices include:

- lending revenues being passed to the investors who take the counterparty risk

- providers should only receive costs for the lending arrangements

- collateral taken from lending counterparties should be fully disclosed and marked-to-market daily

- collateral should be managed by a third-party collateral manager

- eligible up-to-date collateral schedules should be generally available to investors

- any synthetic or swap exposure should have full disclosure of the counterparty(s) and collateral should be posted to cover risk of counterparty default

Where we are today

Crypto asset exchange-traded products (ETPs) are an exceedingly popular vehicle for investors to gain exposure to the price movements of cryptocurrencies like bitcoin (BTC) and ether (ETH).

As of February 2022 there were 73 crypto ETPs in Europe, comprising $7bn in assets under management (AUM), more than 50% of the global total[1].

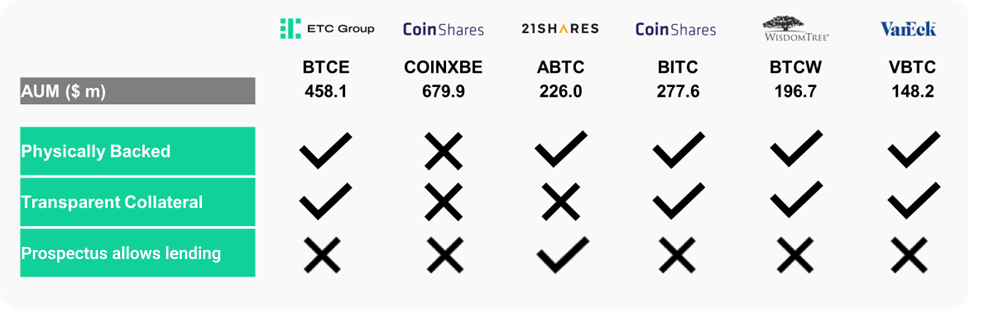

Scanning the list of the leading European crypto ETPs by AUM one would not necessarily immediately notice the difference between them.

These ETPs trade on regulated European stock exchanges, for example Germany’s Deutsche Börse XETRA or the Swiss SIX Exchange.

The larger the AUM and the more liquid the product is, the easier it is for investors and traders to buy in and sell out at the price they require.

The way that issuers structure their products makes an important difference to the risks that investors face.

Each must file a prospectus and final terms with their local market regulator. Once approved, investors can inspect the prospectus, which details the security they are being offered, how it works, and what it is and isn’t allowed to do.

Prospectuses are full of legal jargon and often hard to follow but are, however, extremely important to help investors to make informed choices.

And each provider structures their ETP in slightly different ways.

To lend or not to lend

One major point of difference is whether a crypto ETP chooses to lend out the underlying securities — BTC or ETH for example. In colloquial terms this is often referred to as ‘sweating’ assets: extracting the maximum possible value from AUM by using them to generate additional yield.

In the world of equity ETFs, fund managers will regularly ‘sweat’ or lend out the underlying securities, collecting payments from borrowers and therefore boosting the fund’s returns.

As Emma Boyd writes for the Financial Times: “Securities lending should really be called ‘securities renting’: The owner of the securities ‘lends’ them in return for a fee. While the securities are on loan the borrower transfers collateral in the form of other securities such as shares, bonds or cash to the lender. The value of the collateral is equal to or greater than the value of the securities being borrowed.”

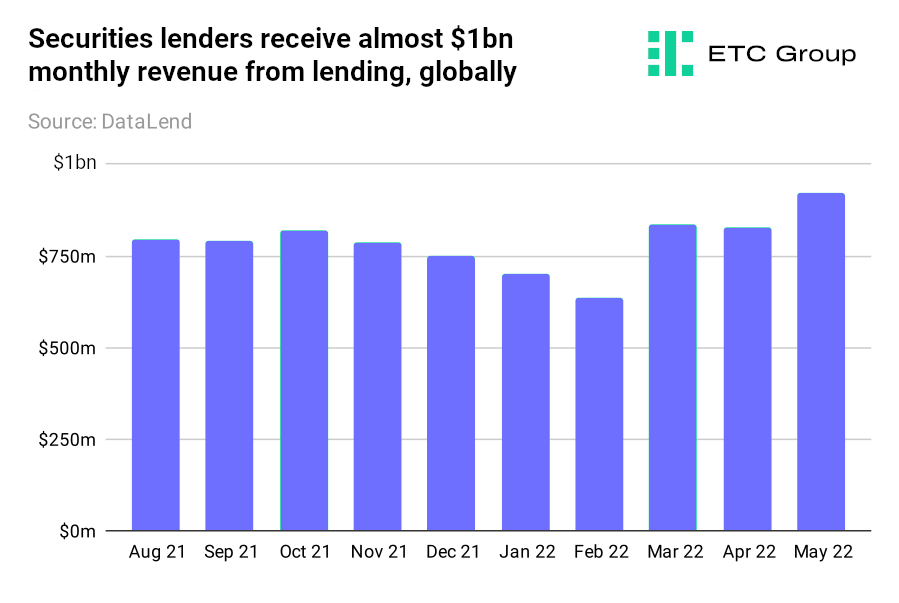

Securities lending is big business. In 2021 the global securities finance industry generated $9.28bn of revenue for those fund managers lending out underlying assets, according to DataLend. The figures for May 2022 were close to $1bn a month.

If investors are unsure about whether a provider allows an ETP or ETF to ‘sweat’ or lend out the underlying assets — and hence to what degree of additional counterparty risk they are exposed — they can look it up in the prospectus for each product.

It must be noted that this practice introduces significant additional counterparty risk. Counterparty risk is the risk that the person or entity who takes the equity on loan won’t pay up when the contract or agreement comes due: when counterparties fail, there is the risk that ETPs, funds or investors won’t get their money back.

Put another way: if a borrower becomes insolvent and cannot return the assets, the money the lender can raise from selling whatever is held as collateral (assuming there is collateral) will not be enough to cover the difference.

The process for crypto ETPs is similar to equities lending: where a prospectus allows a crypto ETP to lend out its assets, the ETP will lend some of its underlying assets to another financial institution. This is usually a crypto lending institution who onwardly lends, meaning the lender often has no idea who the end borrower is. The institution, which is the borrower, pays the lender a fee, and may provide collateral to the lender for borrowing the asset. At the end of the loan, the institution is supposed to pay back the asset in full, with interest.

It is worth mentioning here that rehypothecation in crypto markets is rife, especially amongst lending institutions, adding enormous additional risk to relevant products at times of market stress. Rehypothecation is a term that consistently came up in the fallout from the 2008-9 financial crisis. It effectively means re-using collateral made in one agreement as the basis for new, separate loans with other entities. Put another way, lending institutions re-used collateral put up by clients as collateral tofinance additional transactions.

Due to the complex web of lenders, borrowers and leverage in financial markets, if an underlying entity defaults, it causes enormous stress on the whole financial system, potentially causing a contagion of cascading failures, as we saw in the global financial crisis and have seen recently with a number of high-profile defaults within the crypto industry.

The risk of counterparties defaulting on their obligations is a major point of friction that stops institutional investors from investing in crypto asset products as much as they would like.

Counterparty risk is also more pronounced in crypto markets than in equities because lending is more often uncollateralised and there are fewer risk control measures in place than in the world of equity lending.

In the case of ETC Group, each of its 14 crypto ETPs are physically-backed by the underlying assets (BTC, ETH, SOL etc) and are structured so that the underlying assets cannot be used in lending agreements.

As per its security agreement, ETC Group “will not sell, lease, transfer or otherwise dispose of any of the collateral” contained in its crypto ETPs.

ETC Group’s base prospectus, which governs its entire suite of crypto products, also notes that:

“So long as any Bond remains outstanding, the Issuer will not (except where explicitly permitted under the Terms and Conditions):

- create or permit to subsist any mortgage, pledge, lien, securityinterest, charge or encumbrance securing any obligation of any person (or any arrangement having a likeor similar effect) upon all or any of the Security; or

- transfer, sell, lend, part with or otherwise dispose of, orgrant any option or present or future right to acquire, any of the Security.”

By not sweating assets — loaning them out to borrowers in exchange for fees — ETPs offered by ETC Group remain in an objectively lower counterparty risk position than those that do.

As noted above, the 21Shares Bitcoin ETP is the fourth-largest Bitcoin investment product in Europe by AUM.

In the 21Shares base prospectus is a section that allows the issuer to enter into lending agreements “whereby it lends certain Underlying or Underlying Components to third parties”.

The prospectus also notes that: “In such a case, the Collateral consisting of directly held Underlyings or Underlying Components is replaced by Collateral in the form of a futures contract. In order to mitigate the Issuer’s, and the Investor’s indirect, credit risk exposure to any parties to any lending arrangements, that third party must post eligible collateral assets with a market value at least equivalent to the value of the Underlying or Underlying Components lent.”

“A borrower may not post back additional collateral assets when required or may not return the Underlying asset when due.”

Putting aside the very difficult concept of a futures contract somehow constituting collateral, or the broad definition around eligible collateral assets,the key line in terms of the potential additional risks posed to investors (compared to those products that do not allow lending) is:

“A default by the borrower under such lending arrangements combined with a fall in the value of the collateral assets that borrower has posted back may result in the Issuer holding insufficient assets to meet its obligations in connection with redemptions of Products and a corresponding fall in the value of an Investors holding.”

One other criticism that is often levelled at crypto ETPs is that the additional returns from ‘sweating’ or lending out assets are not always passed on to the people taking the capital risk in the first place: the investors themselves.

And there is little to no publicly available data about how much additional returns are produced from lent assets in crypto ETPs, nor what additional return investors can expect to receive from this process.

Investors in crypto ETPs that allow lending are effectively putting their cash into a black box and having to rely on a provider’s goodwill to manage risk and pass on the gains to them. This is clearly not an optimal investment strategy.

Simply, investors should be able to work out precisely what they are buying, what opportunities each product offers, and any additional risks to which their capital may be exposed.

In a 4 July 2022 article published in the Financial Times, 21Shares CEO Hany Rashwan noted that one of the Swiss company’s new products brought to market, called Bitcoin Core ETP (CBTC), would “opportunistically lend”.

Here, undercutting rivals’ expense ratios is specifically subsidised by the revenue generated from loaning out Bitcoin from the fund. This ignores the fact that the existing 21Shares Bitcoin ETP (ABTC) is issued from the same base prospectus therefore the assets are also available for the issuer to lend, so really this is just the same product with a reduced Total Expense Ratio (TER) that acknowledges some of the risks that investors are taking and rebating some of the benefit.

The article adds: “Rashwan said loans would be over-collateralised, with the collateral — bitcoin, ether or USD Coin, a so-called “stablecoin” — equivalent to at least 115 per cent of the value of the loan and marked to the prevailing market price twice a day. A stablecoin is pegged to a traditional currency like the dollar.”

It is hard to understand how a BTC loan could be collateralised by 115% BTC and make commercial sense, or indeed with ETH or USDC which are consistently more expensive to borrow. Without a clearly defined collateral schedule baked into final terms, such products should make investors wary.

One final point to make is that the collateral that is used as backing for loans is normally meant to be comprised of assets uncorrelated to the asset being loaned. Take for example repo markets (bank-to-bank overnight repurchase agreements). The assessment of the International Capital Markets Association, in a 2019 report, was that: “collateral issued by a party whose credit risk is uncorrelated with that of the repo seller will diversify exposure and avoid so-called ‘wrong-way risk’, which is the danger of the collateral value falling as the creditworthiness of the seller deteriorates.”

Unsecured loans – those generated without any collateral backing – remain even riskier, but still comprise a hefty proportion of the lending market in traditional finance. According to the European Central Bank, the EU market for unsecured loans totals around €140 billion per day.

Cryptocurrency prices are notoriously volatile. Since March 2020 the price of Bitcoin careened up from $5,000 to $69,000 in November 2021 and as of July 2022 is trading in spot markets at around $19,500. This makes Bitcoin risky collateral against loans, and is why lenders often demand cryptocurrency collateral that exceeds the value of the loan (over-collateralised loans).

Risk overexposure

Crypto markets are currently experiencing significant stress, with severe strife hitting their lending verticals.

In the above Financial Times article Rashwan describes over-collateralised loans as “incredibly safe”. It must be noted that even with over-collateralised loans there still remains the risk of borrowers defaulting, especially as cryptocurrency markets are currently undergoing a credit crisis.

One of the latest high-profile victims of this crisis is Singapore-based hedge fund Three Arrows Capital, which filed for Chapter 15 bankruptcy in the United States having defaulted on a loan worth more than $670m from Canadian broker Voyager Digital.

It is also not yet clear at this stage the extent to which those businesses that do engage in lending are exposed to other risky loans or troubled companies. This makes a new ETP product that is deliberately built around lending out crypto assets an especially high-risk measure at this point in time.

Crypto ETPs a growing market

As Bloomberg Intelligence wrote in December 2020: “Cryptocurrency-linked exchange-traded products in Europe have surpassed 1 billion euros in assets this year, a level that we believe cements the category as a serious driver of industry growth. Strong demand for the strategies is overcoming access hurdles and a recent regulatory ban on selling such ETPs to retail investors in the UK.”

Beyond Europe, the picture is even more impressive.

CryptoCompare’s Digital Asset Management Review for February 2021 noted that total global AUM in crypto ETPs had reached $44bn. And projecting out to 2028, Bloomberg Intelligence’s 2022 Crypto Outlook research report suggested global AUM in crypto ETPs could reach as much as $120bn over the next six years.

The risk issue with securities lending

Because there has been such a major shift towards passive investing strategies over the past 30 years, the demand for borrowing the assets underlying ETFs or ETPs — whether that is crypto assets, bonds, or equities like stocks and shares — is growing exponentially.

As data provider IHS Markit notes in ‘Why it pays to lend ETFs’: “A quarter of the 2,200 ETFs that feature inside lending programs have over half their inventory out on loan.”

By 2017 some 20% of ETF assets— worth $38bn (€38.4bn)— were on loan, compared to 8% of common stock, proving this strong borrowing demand.

Who benefits from the additional fees that lending out assets accrues is still a point of contention. Professional bodies have been arguing for the best part of a decade that fees from securities lending should go to fund investorsrather than to the managers.

The Investment Association (IA) for example, has 250 members managing £9.4trn (€10.9trn) for investors in the UK and around the world.

A 2012 survey by London wealth manager SCM Private that found half of the largest UK fund managers lent out stock, pocketing a third of the income generated. In response, IMA director Julie Patterson noted: “Frankly, [the stocks being lent] are the fund’s assets [and] don’t belong to the fund manager.”

This brings up to two specific points. First, while securities lending in non-crypto markets has been a standard industry practice since the 1960s, the benefits and the profits these processes accrue were once largely confined to fund managers and asset managers themselves, rather than the individual investor. Thankfully this has since changed, following intense pressure from regulators and investors.

In 2012, the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) issued guidelines to the operators of ETFs which included a requirement to give all lending profits, after costs, to their funds.

One important obligation prescribed by these ESMA guidelines was also the requirement to clearly disclose relevant information on the conflicts of interest and counterparty risks that stem from the use of securities lending.

Second, and more importantly, the details of how much the end investor actually accrues from an ETF manager or ETP provider lending out assets is often obscured or difficult to work out.

Synthetic versus Physical

CoinShares, through its Swedish subsidiary XBT Provider AB, launched its Bitcoin Tracker Euro product on 10 May 2015 as a Certificate trading on Nasdaq OMX in Stockholm. Its prospectus states that:

“To hedge its exposure under the certificates, XBT Provider (the Issuer) enters into an intra-group collateral management arrangement with the Guarantor (CoinShares Capital Markets) as follows:

- The issuer provides cash raised from the issuance of the Certificate to the CoinShares Capital Markets

- The Guarantor promises to pay the settlement amount of the note (the original purchase price plus or minus any price movements in the underlying crypto currency less a fee)

- To hedge its exposure under that contract, the Guarantor purchases the relevant crypto currency on a 1:1 basis, in both physical form and using derivative contracts.

There are additional risks for investors to consider if they put their money into a synthetic product as opposed to a physical one.

CoinShares’s Bitcoin Tracker Euro (COINXBE) is the largest Bitcoin investment product in Europe by AUM. It is structured as a synthetic, rather than a physical product.

While a physical ETP replicates the performance of an index or product by physically holding the underlying asset, a synthetic version replicates the performance of an index or product by relying on derivatives called swap agreements with a counterparty (a crypto asset lender, such as Celsius, Nexo or in the case of COINXBE and others, an affiliate). The provider enters into a deal with the counterparty, who promises that the swap will return the value of the index an ETP tracks.

The returns of a synthetic product thus depend on a counterparty being able to honour its commitments. This exposes investors in synthetic products to counterparty risk. Again, this is the risk that the entity on the other side of an agreement will not be able to pay their debts.

And as the European Central Bank (ECB) notes:

“Apart from being exposed to market and liquidity risk…investors bear counterparty risk in [exchange traded products] using derivatives or engaging in securities lending. Synthetic ETF investors are therefore exposed to counterparty risk, ie, the risk of loss from a default of the counterparty. Physical [exchange traded products] that lend securities from their portfolios also expose their investors to counterparty risk. In this case, investors might suffer losses if a borrower defaults on its obligations.”

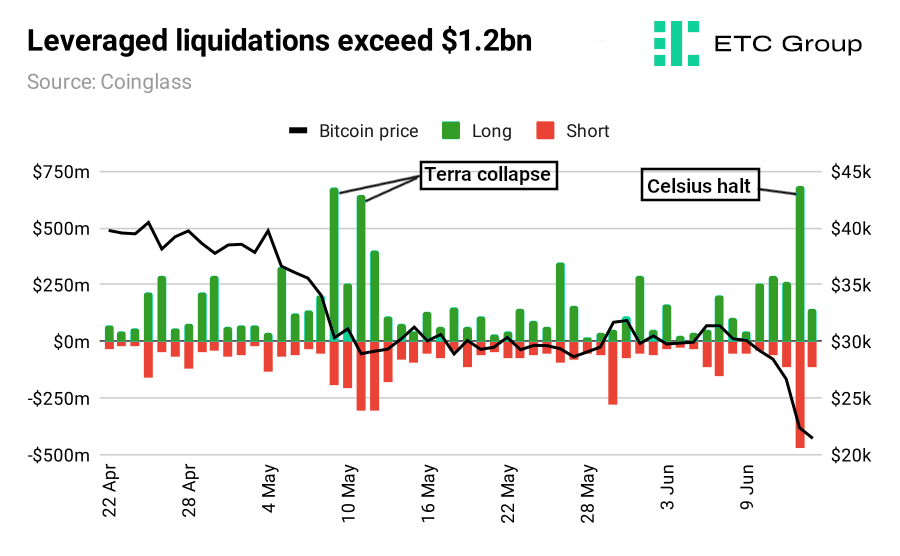

Counterparty risk can be mitigated by the collateral that an exchange traded product holds. But in the case of single-asset crypto ETPs, when there is a large drop in the market price of an underlying asset, as for example when Bitcoin lost 20% of its value over the course of five days in mid-June 2022, this situation will usually trigger a margin call which could put intense pressure on the issuer to meet their demands in a timely manner, and in extreme cases could lead to default.

There is also the issue of a negative feedback loop from large redemptions that can affect investors more broadly.

“Factors related to market structure and investor behaviour may amplify the effects of materialising counterparty risk on financial stability, the ECB adds. “[T]here is a high level of concentration of counterparties of synthetic ETFs in Europe. While counterparties are typically connected with many ETFs, most ETFs rely on a single counterparty.”

The sole swap counterparty to COINXBE is understood to be Coinshares International, a proprietary trading firm within the CoinShares group.

A Q1 2022 research note from Edison Group, commissioned by CoinShares, notes that:

“[CoinShares International] will report a $17m exceptional loss in Q2 22 arising from its exposure to the Anchor protocol due to the collapse of the UST stablecoin.”

This highlights some of the counterparty risks associated with synthetic products.

Lenders sweat as Celsius halts

On 13 June 2022, crypto lender Celsius announced it was halting all withdrawals, swap agreements and asset transfers, citing “extreme market conditions”. As of early June, the lender had around $12bn in assets under management.

More than a week after its halt, the lender said in a 20 June Medium post that it needed more time to stabilise liquidity, and as of a 30 June update gave no updated timeline for when its services might resume.

Trader sentiment was already struggling in the face of a 50%+ drawdown from November’s speculative run up to a Bitcoin $68.7k all-time high. Markets were bruised but looking resilient after the Terra-induced collapse of mid-May.

But as Bitcoin shed 20% of its value against the US dollar over the course of a week, attitudes turned markedly more bearish. Within a matter of hours, the $4.5bn AUM crypto lender Nexo had swooped in with a buy offer for Celsius’ collateralised loan portfolio.

Nexo publishes real time attestation of its assets and liabilities.

The Wall Street Journal published on 15 June 2022 that Celsius had hired restructuring lawyers, while comments from crypto market data provider Kaiko noted that “a large number of withdrawals has severely stressed Celsius’s liquidity, particularly after the rumoured losses the platform suffered in the Terra collapse last month…The team did not provide any information on when withdrawals would be enabled”.

A day later, Kaiko research analyst Conor Ryder suggested that the Celsius halt had spread “widespread panic that the company was insolvent.”

“Crypto markets are crashing and certain companies that have taken on excessive risk are facing the consequences,” he wrote. “How did such large companies that are intertwined with the industry’s biggest market participants end up in a Lehman-esque position?”

A combination of poor risk management on the part of Celsius and bearish market conditions contributed to “a perfect storm with potentially devastating consequences”, Ryder said, with time running out for Celsius to prove they were not insolvent.

It became clear after Celsius users sought increasingly large redemptions that the lender would struggle to meet them — playing out the counterparty risk theory in real time.

In the wider derivatives trading markets, we have now witnessed two $1bn+ leveraged liquidation events inside 35 days: on 11 May 2022 with Terra and 13 June 2022 with Celsius.

In a sign of growing crypto contagion, the Financial Times reported on 16 June 2022 that embattled hedge fund Three Arrows Capital (3AC) had failed to meet its lenders’ margin calls.

In a statement posted to social media Nexo said that it had “zero exposure” to the hedge fund. “Оver 2 years ago, we declined 3AC’s request for unsecured credit. We learned that they acquired it elsewhere. It is now obvious that Nexo’s approach was correct. This is why our assets exceed our liabilities.”

In this changed crypto market environment, conservative approaches to capital management are starting to look more attractive.

Are Bitcoin ETFs coming to Europe?

Finally, the structure of new crypto investment products coming to market requires closer analysis. One recent product, launched with a 30 June 2022 press release, comes to mind.

In a note supporting the launch of a new Bitcoin ETF on Euronext Amsterdam, the CEO of Jacobi Asset Management Jamie Khurshid, says:

“For those who have been misinformed and misled, intentionally or otherwise, by the incorrect use of the term ETF, or the group term ETP to hide the fact that the instruments themselves are ETNs, I can clarify:

“The only similarity between our Bitcoin ETF and the various Bitcoin ETNs available is that they are all traded on exchanges and are therefore collectively known as exchange-traded products (ETPs). Misuse of the term ETF by ETN issuers only serves to obfuscate the risks in acquiring and investing in debt instruments like ETNs. With an ETN the investor is acquiring unsecured debt and is at risk of losing their investment should the debt issuer fail, for example, through overexposure to other more risky digital assets.”

Insofar as the majority of crypto ETPs in Europe are structured as bonds, they are not ETNs in the classical sense (though definitions are used broadly, they could be considered as ‘physically-backed ETNs’). An ETN is generally a note issued by a financial institution that promises to pay the holder a defined outcome — in the simplest case the price return of an asset — also known as Certificates. These products are unsecured and the holder faces the credit risk of the issuer. And there are such products available in Europe on a wide range of assets, including bitcoin.

This is not generally what crypto ETPs are – they use a structure that was invented over a decade ago which was initially brought to market for physical commodity products such as gold (the largest of which today is the iShares Physical Gold ETC with over £13bn in AUM, suggesting a degree of institutional acceptance). These are physically-backed securities or bonds, 100% secured by the underlying asset. They were created for assets ineligible under UCITS rules or products that failed to meet UCITS diversification criteria (such as individual precious metals).

The degree of security, as with all funds/investment products such as these, requires investors to look closely at the prospectus and the final terms. Khurshid highlights in a website post that the Jacobi Bitcoin ETF product “is fully collateralised with absolutely no leverage. Investor funds and the fund assets themselves cannot be rehypothecated or lent out to anyone for any period of time.”

When looking at ETC Group’s suite of crypto products, investors will find the same to be true.

But as noted above, this is not always the case with regards to other ETP issuers.

What isn’t so obvious from these statements, is that this Jacobi ETF isn’t a standard UCITS ETF, in fact it’s not governed by UCITS at all. It is an open-ended collective investment scheme authorised as a Class B Scheme by the Guernsey Financial Services Commission. The Jacobi prospectus also states that “in giving this authorisation the Commission does not vouch for the financial soundness of the Company or for the correctness of any statements made or opinions expressed with regard to it.” There is nothing wrong with that, but it is perhaps not what an investor would expect when they hear the term ETF used in Europe.

The fee structure is also highly complex with more than a dozen individual sources of charge made against fund assets, although it is capped at 150 basis points. This, however, ignores establishment costs (capped in $USD) which are amortised over three years against the assets of the fund, directors’ remuneration (capped in £GBP) and directors’ expenses (which are largely undefined and uncapped), all of which are also charged to the fund. So, despite the above claims, there is no real way for investors to know precisely what they are paying, and the structure of this fund is not as transparent as it could be.

Key Takeaways

- The rapid growth of crypto ETPs in Europe and beyond has provided a regulated and secure way for investors to gain exposure to the price movements of cryptocurrencies. However, the structure of a particular crypto ETP may expose investors to significant additional counterparty risks.

- The risk of counterparty default is more prominent in crypto markets than in equities, because lending is more often uncollateralised and thereare fewer risk control measures in place and much less transparency with regard to underlying collateral arrangements.

- The benefits of securities lending are often touted (improved liquidity, improved market efficiency, improved returns) while the additional risks are often glossedover, and the returns from this practice may not reach investors themselves. Lending revenues should be passed fully less costs to the ETP investor. This is accepted in the ETF market and is shown asout performance.

- More transparency is needed to aid investors in their investment decisions. But it is essential that investors pay close attention to product documents when assessingthe true risks associated with individual products. Now, more than ever, the DYOR principle holds true. Do Your Own Research.

Notes

Important information:

This article does not constitute investment advice, nor does it constitute an offer or solicitation to buy financial products. This article is for general informational purposes only, and there is no explicit or implicit assurance or guarantee regarding the fairness, accuracy, completeness, or correctness of this article or the opinions contained therein. It is advised not to rely on the fairness, accuracy, completeness, or correctness of this article or the opinions contained therein. Please note that this article is neither investment advice nor an offer or solicitation to acquire financial products or cryptocurrencies.

Before investing in crypto ETPs, potentional investors should consider the following:

Potential investors should seek independent advice and consider relevant information contained in the base prospectus and the final terms for the ETPs, especially the risk factors mentioned therein. The invested capital is at risk, and losses up to the amount invested are possible. The product is subject to inherent counterparty risk with respect to the issuer of the ETPs and may incur losses up to a total loss if the issuer fails to fulfill its contractual obligations. The legal structure of ETPs is equivalent to that of a debt security. ETPs are treated like other securities.

About Bitwise

Bitwise is one of the world’s leading crypto specialist asset managers. Thousands of financial advisors, family offices, and institutional investors across the globe have partnered with us to understand and access the opportunities in crypto. Since 2017, Bitwise has established a track record of excellence managing a broad suite of index and active solutions across ETPs, separately managed accounts, private funds, and hedge fund strategies—spanning both the U.S. and Europe.

In Europe, for the past four years Bitwise (previously ETC Group) has developed an extensive and innovative suite of crypto ETPs, including Europe’s largest and most liquid bitcoin ETP.

This family of crypto ETPs is domiciled in Germany and approved by BaFin. We exclusively partner with reputable entities from the traditional financial industry, ensuring that 100% of the assets are securely stored offline (cold storage) through regulated custodians.

Our European products comprise a collection of carefully designed financial instruments that seamlessly integrate into any professional portfolio, providing comprehensive exposure to crypto as an asset class. Access is straightforward via major European stock exchanges, with primary listings on Xetra, the most liquid exchange for ETF trading in Europe.

Retail investors benefit from easy access through numerous DIY/online brokers, coupled with our robust and secure physical ETP structure, which includes a redemption feature.

En

En  De

De