Bitcoin, ESG and the Future

How crypto works in the age of climate crisis

How crypto works in the age of climate crisis

The sustainability of investments is no longer simply desirable. It is becoming obligatory. In the face of the Paris Agreement, the legally binding international treaty which seeks to avoid the most damaging effects of climate change by limiting global warming to below 2°C, there is renewed focus on environmental and ethical investing.

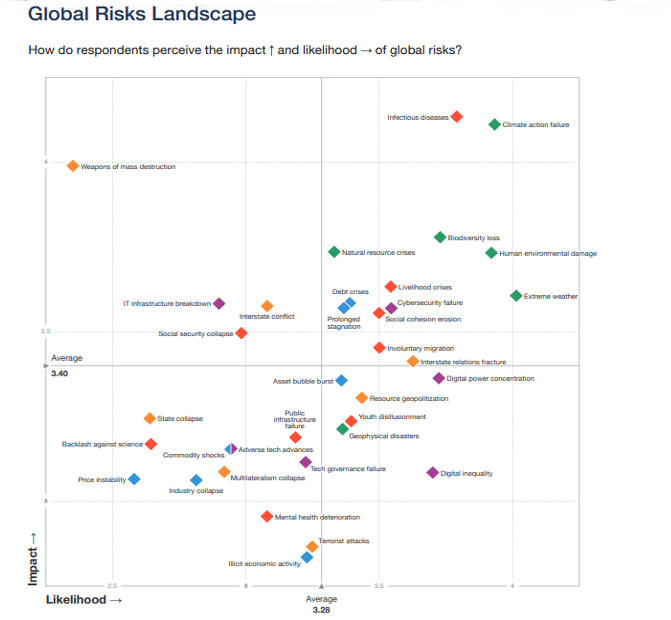

The World Economic Forum’s annual report on global risks puts largely climate-based concerns at the top of the biggest threats facing humanity.

Climate change— to which no one is immune— continues to be a catastrophic risk... Most critically, if environmental considerations— the top long-term risks once again— are not confronted in the short term, environmental degradation will intersect with societal fragmentation to bring about dramatic consequences.

In terms of the highest impact and likelihood of risks — alongside the unsurprising new entrant infectious diseases — the top five include: climate action failure, human environmental damage, biodiversity loss and natural resources crises.

ESG investing, which seeks to put Environmental, Social and Governance impacts at the heart of investment decisions, is also drawing in vast amounts of capital. Recent research by distributed ledger-based institutional trading network Calastone suggest that ESG-focused investments accounted for a staggering 84% of all equity investments since 2019, a total of $15.1bn out of $18.1bn of net inflows into equity funds. UK and European investors showed the largest interest in ESG funds, its April 2021 report found. The value of global assets applying ESG data to drive investment decisions more than tripled to $40.5trn between 2012 and 2020, and the size of ESG teams in the top 30 global money managers has grown by 229% since 2017, according to research by Opimas.

On 10 March 2021, the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosures Regulation entered into force, requiring investment funds to disclose if and how sustainability risks are integrated into their investment process. This puts intense pressure on fund managers to steer clear of potential investments without sustainability at their heart.

Where, then, does this leave Bitcoin and digital assets? Anecdotal evidence suggests that only a small proportion, possibly as few as 10% of fund managers, are investing in Bitcoin and other cryptoassets because of concerns about their environmental impacts. For most investment managers it has certainly been hard to avoid global headlines like Bitcoin ‘consumes more electricity than Argentina’.

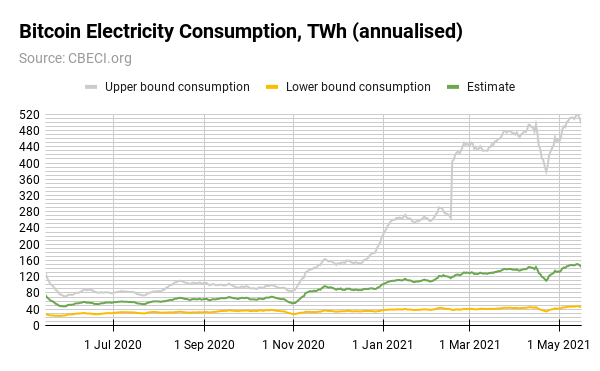

Almost all media reporting of Bitcoin’s electricity usage comes from the Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index (CBECI), run by the University of Cambridge Judge Business School. It applies a statistical method of theoretical upper and lower consumption bounds to produce an estimate of the daily power usage required to maintain the Bitcoin network, which is then extrapolated out to an annualised amount ( Figure 1). As of 17 May 2021, this estimate sits at 12.93GW, producing an annualised 144.28TWh (Terrawatt-hours), or around 0.69% of total global electricity consumption worldwide.

Powerful intergovernmental organisations like the OECD have already recognised blockchain’s potential to aid authorities in shifting financial flows to lower-emission and more resilient infrastructure, which they observe is critical to delivering on climate and sustainable development goals. Indeed, its Financing Climate Futures: Rethinking Infrastructure report, produced alongside UN Environment and the World Bank Group, offers a roadmap to help nations to transform their infrastructure in light of such technological developments.

One case study from the 2019 report suggests that emissions certificate trading systems:

... could be made more efficient by providing transparency and reliable data through a global blockchain layer… to effectively control quota rules, certificate circulation, promote market integrity and robust carbon accounting while also automating transactions and increasing overall efficiency. Regulatory, compliance, and administrative functions can be codified in the system, creating a transparent book of accounts on emissions. A blockchain-enabled platform could also link treaty-level registries in support of the Paris Agreement, particularly relating to Articles 2.1c and 6.

The near-term picture for the cryptoasset sector has been complicated by recent social media posts by Tesla (NASDAQ:TSLA) CEO Elon Musk, catalysing intense debate about the ESG properties of Bitcoin and digital assets.

Tesla first waded into the debate with a $1.5bn Bitcoin purchase, as filed with the SEC on 8 February 2021, before announcing that it would accept Bitcoin as a payment method on 24 March. On 12 May Musk tweeted that Tesla will no longer accept bitcoin as payment for its electric vehicles

Tesla has suspended vehicle purchases using Bitcoin. We are concerned about rapidly increasing use of fossil fuels for Bitcoin mining and transactions, especially coal, which has the worst emission of any fuel. Cryptocurrency is a good idea on many levels and we believe it has a promising future but this cannot come at great cost to the environment. Tesla will not be selling any Bitcoin and we intend to use it for transactions as soon as mining transitions to more sustainable energy. We are also looking at other cryptocurrencies that use <1% of Bitcoin’s energy [per] transaction.

Attempting to parse Elon Musk’s recent response to Bitcoin, a cynic could allege firstly, that the Tesla CEO knows full well that he wields outsize power in influencing retail investors and secondly, that his well-publicised Dogecoin holdings may form the ‘other cryptocurrencies’ he mentions in his statement. Dogecoin, incidentally, is a fork (copy) of Bitcoin which uses precisely the same proof-of-work system to secure its network but without the same deflationary hard cap on its coin supply

Certainly the entrepreneur, with his penchant for market-moving statements, has helped create excessive short-term volatility in the price of bitcoin, and with a weak technical response to a dip below $44,000, the cryptocurrency was in correction territory as of 17 May. Any decision to criticise Bitcoin for using electricity shows extreme cognitive dissonance and is at odds with Tesla’s stated aim: to move the automotive sector onto electric power and support this seismic shift by building vast Gigafactory battery farms.

There’s no doubt that Bitcoin does consume resources, like any other industry. And the extent of its energy use is a debate worth having.

But the metric of a ‘per-transaction’ energy cost, as criticised by Elon Musk, is itself misleading, according to Nic Carter, CoinMetrics co-founder and the first cryptoasset analyst for asset management giant Fidelity Investments. Writing for the Harvard Business Review in May 2021, he says:

The vast majority of Bitcoin’s energy consumption happens during the mining process. Once coins have been issued, the energy required to validate transactions is minimal. As such, simply looking at Bitcoin’s total energy draw to date and dividing that by the number of transactions doesn’t make sense — most of that energy was used to mine Bitcoins, not to support transactions.

Still, Musk’s cryptic tweets do speak to a wider conversation that fund managers and asset managers are having to conduct: do Bitcoin’s ESG credentials make it undesirable to invest in? Ernst & Young Global Blockchain Lead Paul Brody told industry news website Coindesk that he has been having the same conversation about cryptocurrency’s energy consumption since 2017.

We have so many enterprise clients that care about this topic. Quite a few enterprise clients have held off on doing stuff in blockchain over their concerns about the carbon footprint.

What is clear is that the megatrends of ESG and digital assets are colliding in spectacular fashion as we head further into 2021.

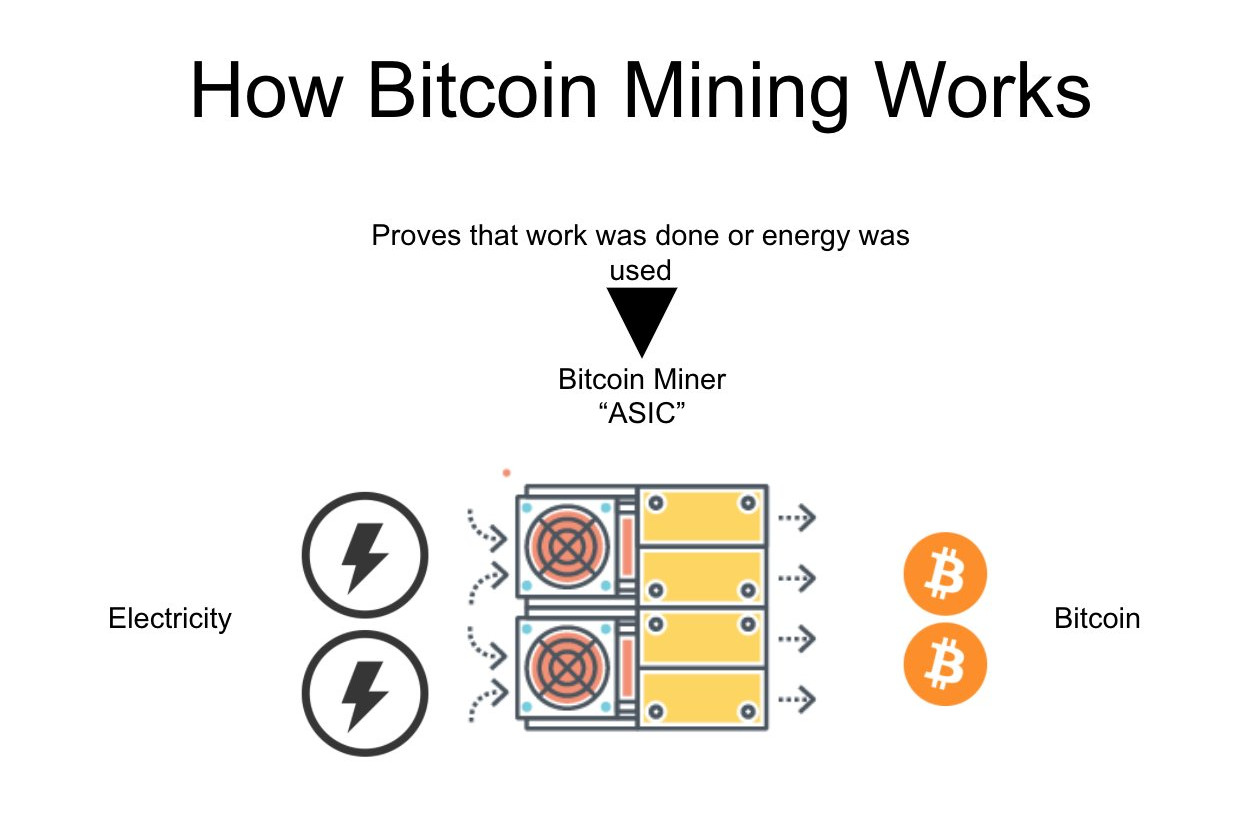

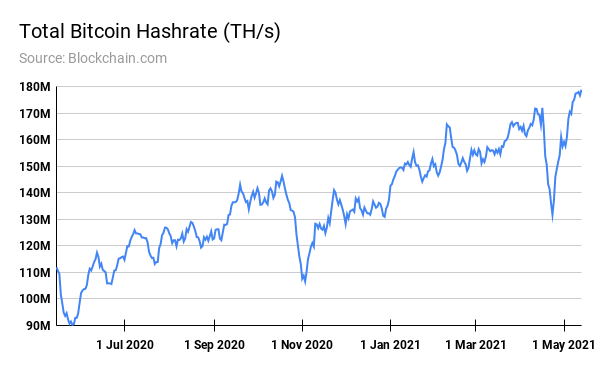

Bitcoin’s network is secured by a type of cryptographic algorithm called SHA-256. Its ‘hashrate’ is a calculation of the total combined computing power used to mine and process transactions. Effectively, this is the speed at which mining machines run their algorithms to compete for new issuances of bitcoin. The more hashing power in the network, the greater its security and the greater resistance it has to being attacked.

Hashrate is denoted using the unit prefix multipliers giga- (G), tera- (T), peta- (P), exa- (E) etc. where one Terahash (TH) is 1,000 Gigahashes, 1 Petahash (PH) is 1,000 Terahashes, and 1 Exahash (EH) is 1,000 Petahashes.

Because Bitcoin is a proof-of-work blockchain, the faster a computer can process calculations (the ‘work’), the more likelihood that machine has of being rewarded in bitcoin. In the early days of cryptocurrency, a home computer could run calculations fast enough to be in with a chance of winning block rewards (currently 6.25BTC per block). As competition ramped up, by 2013 specialist Application Specific Integrated Circuit (ASIC) machines were developed for the singular purpose of Bitcoin mining, with Bitmain’s Antminer the industry-standard machine.

One of the unintended consequences of the proliferation and growth of the Bitcoin network — and the bitcoin price — is that intense competition has sprung up between miners in order to compete for the rewards distributed in BTC. Mining pools — vast agglomerations of combined computing power — are the result of this competition.

The difficulty for fund managers today who are considering ESG in terms of digital assets is the arduous task of separating fact from fantasy over Bitcoin’s power usage.

Elon Musk’s assertion that there is a “... rapidly increasing use of fossil fuels... especially coal” in Bitcoin mining is misplaced given what we know about recent trends. In the main, it comes from the idea that coal-dominated China is controlling an ever-greater majority of the Bitcoin hashrate, because of the country’s cheap electricity prices and large areas of unused land make it a perfect destination for miners to set up. China’s energy mix is also quite clearly defined: miners tend to rely on renewable hydropower in the rainy season before switching to coal and natural gas in the dry season.

What these high-level hashrate estimates do not show are the power sources used to create this electricity usage.

While determining energy consumption is relatively straightforward, you cannot extrapolate the associated carbon emission without knowing the precise energy mix - that is, the makeup of different energy sources used by all the computers mining Bitcoin. For example, one unit of hydro[power] energy will have much less environmental impact that the same unit of coal-powered energy. — Nic Carter, Harvard Business Review, 5 May 2021

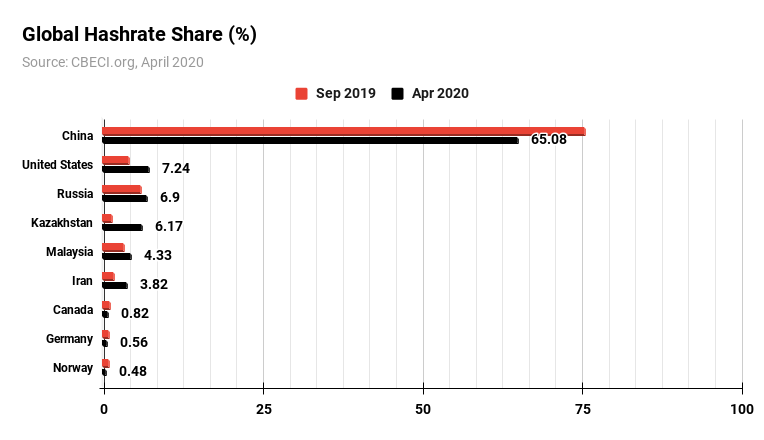

Part of the main conversation about Bitcoin energy usage is which country controls the highest portion, and therefore which energy sources (wind, solar, natural gas, coal etc) are most likely to be used to maintain the greatest proportion of the Bitcoin network.

Again, the vast majority of media reporting uses figures from the CBECI. It uses aggregate geolocation data, based on the IP address of hashers connecting to mining pools.

What is less widely known is that, unlike their Bitcoin electricity usage estimates, which are updated every 30 seconds, the CBECI only maintained its country-level hashrate date up to April 2020. And the methodology is based on several assumptions that readers may or may not agree with, chiefly that the sample is based on only 37% of the total Bitcoin hashrate as recorded at the time, and that data was provided to the CBECI by only three Bitcoin mining pools that are all headquartered in China. So the dataset does not include all mining pools by any stretch, nor is it up to date, leaving analysts largely in the dark about the true state of affairs.

Finally, as noted in the limitations small print by the CBECI:

It is no secret in the industry that hashers in certain locations use virtual private networks (VPNs) or proxy services to hide their IP address and thus location. Such behaviour may distort the overall geographic distribution and result in an overestimation of hashrate in some provinces or countries.

In the time period surveyed, Chinese control of the Bitcoin hashrate dropped from ~75% to ~65%, while North American sources (Canada and the US) rose from 5.12% to 8.06%.

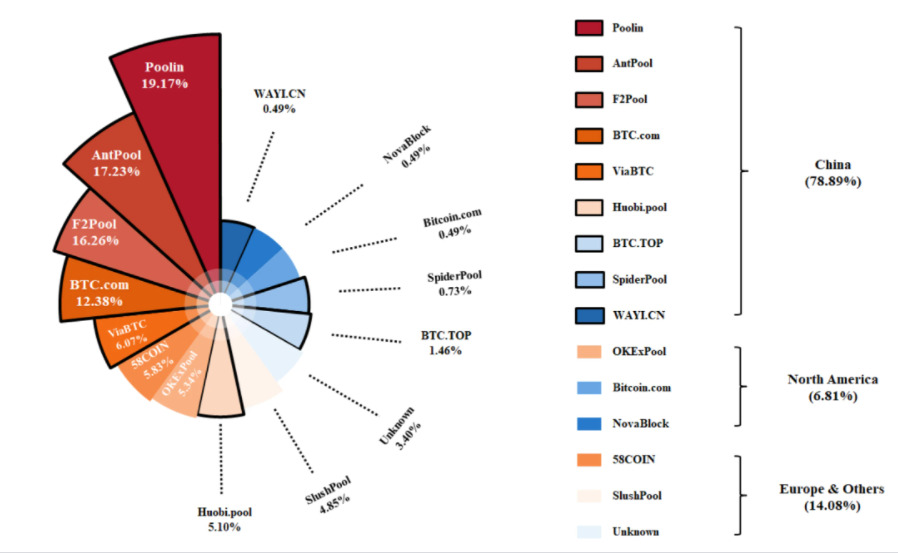

A widely-cited paper, ‘Policy assessments for the carbon emission flows and sustainability of Bitcoin blockchain operation in China’ , published in the Nature Communications journal on 6 April 2021 by a team of Chinese researchers, uses a figure of 75% for China’s dominance of the mining market, apparently based on the CBECI April 2020 data. And repeating this dubious figure for example, is the Australian Financial Review in a 7 April 2021 piece entitled ‘China’s control of bitcoin mining terrifies investors’.

That such claims are repeated verbatim does not, perhaps, serve to advance the conversation in any meaningful way. One could also infer from what we know about this general trend that China’s share of hashrate has declined further than reports using these out-of-date statistics suggest.

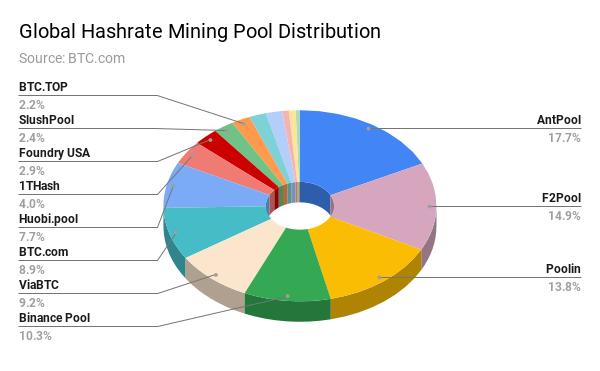

Compare, for example, the mining pool chart cited in Nature Communications (Figure 5, below) with an up-to-date model showing that Foundry USA controls approximately 2.9% of the global Bitcoin hashrate, the ninth-largest globally (Figure 6, below).

Foundry USA, incidentally, is run by the Digital Currency Group, which owns Coindesk, Grayscale Investments, and Genesis. It opened Foundry USA to institutional clients in March 2021 after around six months in private beta. New entrants include BitDigital, which added 280 Petahashes of power to the pool in early May 2021. Figure 5 is based on much more up-to-date information and shows the seven-day average of which mining pools control what percentage of the global hashrate.

The exact proportion of renewable energy used to secure the Bitcoin network is likely to remain indiscernible, but as researcher Hass McCook suggests, basic economics dictates that miners will continue to chase the cheapest power available, and this is increasingly becoming renewable.

Supporting the assertion that Western countries, especially in Canada and the US, control a greater proportion of the bitcoin hashrate than is generally reported, is the fact that US institutional investors have purchased at least half a billion dollars-worth of ASIC mining machines in recent months. Reports and studies showing China’s SHA-256 hashrate dominance dropping are starting to appear, too. Recent estimates put China’s dominance closer to 50% than the 65% from CBECI’s April 2020 figures.

There are further signs that Bitcoin will become less reliant on Chinese hashrate over time. Under Xi Jinping, Beijing has incentivised a major curb on carbon emissions from coal-fired plants and has accelerated efforts to force its major provinces to cut their energy consumption. Under the same policy intervention, China has banned the approval of any new mining hubs in one of its largest regions, Inner Mongolia, which accounted for more than 8% of global Bitcoin hashrate as of April 2020. Existing mining operations had until April 2021 before being shut down, and in their place Inner Mongolia has vowed to increase its share of renewable energy capacity by installing more than 100GW of renewables-only electricity generation by 2025.

When comparing Bitcoin to almost any other major international industry, the argument that it is preternaturally damaging for the environment starts to fall down. For example, it is a difficult sell for base or precious metals miners to claim strong ESG values, and these sectors may contribute to the kind of irreversible environmental and biodiversity damage that the World Economic Forum puts at the top of its global risks.

Should asset managers hedging with commodity futures, for example, note that the largest open-pit copper mine in the world, the Kennecott Copper Mine in Utah owned by FTSE 100-listed multinational miner Rio Tinto (LSE: RIO), has cut a ugly scar so wide and deep in the earth’s crust that it can be seen from the International Space Station? Or that the same company destroyed the 46,000-year-old Jukkan Gorge cave in Western Australia, a site of global historical importance, by blasting to expand its iron ore operations?

Gold would appear to be a reasonable analogue to Bitcoin, performing as it does many of the same store-of-value properties, as a global hedge against inflation or downturns in equities or other asset classes. But there remains is a curious gap in reporting over the ESG properties of gold versus Bitcoin.

Gold mining, by any standard, produces far worse environmental effects than cryptocurrency.

Global environmental nonprofit Earthworks notes:

Gold mining is one of the most destructive industries in the world. It can displace communities, contaminate drinking water, hurt workers, and destroy pristine environments. It pollutes water and land with mercury and cyanide, endangering the health of people and ecosystems.

Around 50% of the world’s gold demand comes from jewellery, a luxury item with questionable intrinsic value, and producing enough gold for a single 8 gram wedding ring generates 20 tons of waste, according to recent Life Cycle Assessment research report by DePaul University. Researchers note that the process required is equivalent to about 288kg of CO2 and for every gram of gold mined, more than 35kg of CO2 equivalent are released into the atmosphere. It is also worth noting the difference between the Life Cycle Assessment of an electric bike with mining for gold in terms of its global warming impact.

According to a life cycle assessment completed in China in 2005, an electric bike has a global warming impact of 8,991.186kg CO2 [equivalent] during its production stage. This means the global warming impact produced due to the mining of metals for the 8g wedding ring is about 3%, of the CO2 [equivalent] released from the production of an electric bike. While this comparison doesn’t seem that persuasive consider the average weight of an electric bike with a lithium battery, which is 44.1 lb., compared to the 8g wedding ring (0.01764 lb.). The wedding ring is only 0.04% of the weight of the electric bike, yet the global warming impact of the ring is 3% of that of the electric bike.

And aside from the requirement to build infrastructure, roads, bridges and the like in often remote areas, and the use of almost-entirely diesel-powered generators and trucks to maintain and supply these mines, according to peer-reviewed research in the Chemistry Europe journal, small scale artisanal gold mining accounts for 37% of global mercury pollution, with the heavy metal used to purify small-grain gold found in river systems in Southeast Asia and South America. Researchers write:

Mercury has the capacity to amalgamate elements such as gold, silver and copper into an alloy. The key next step is to burn off the amalgam so that mercury evaporates and gold is left behind. This simple process does not require much investment in equipment, but is extremely toxic. The waste tailings are simply dumped. This procedure is used by millions of artisanal miners.

Artisanal miners produce some 20% of the world’s gold supply, according to recent estimates.

The World Gold Council says around 3500 tonnes of gold was mined in 2020, with 1,300 tonnes of gold recycled. Each kilogram of recycled gold produces 37 tonnes of CO2 and 31.3 MWh of energy. Using these figures, as reported by Hass McCook, gives gold mining an annual energy use of approximately 265TWh, more than double that of Bitcoin.

Where, then, are the ESG concerns about gold ETCs? Some are willing to put their head above the parapet. As Jordan Sriharan, head of the managed portfolio and passive services at Canaccord Genuity, telling ETFStream: “Gold and ESG are not natural bedfellows.”

The London Bullion Market Association’s Responsible Sourcing programme was introduced in 2012, attempting to impose minimum standards on gold production, ensuring conflict-free gold. However, some experts still deride gold as an ESG investment.

From an environmental standpoint, there can be no debate on the high cost to the environment, not least due to the high water usage in mining. The other factor that works against gold being considered ESG is its fungibility and history. While some gold ETCs avoid gold that was refined pre-2012, the gold market is still largely fungible. Is owning a gold bar mined and refined in 2018 better than one from 2000 when they both trade at the same price? — Andrew Liberis, senior associate, Omba Advisory & Investments

A November 2018 Coinshares report using data sourced from Deutsche Bank, Morgan Stanley, the Energy Information Administration and the Chinese National Energy Agency suggests that 78% of Bitcoin’s electricity usage is from renewables,

in stark contrast to the assumptions cited in the media on Bitcoin mining emission and subsequent impact on the environment, whose argumentation presupposes exponentially accelerating requirements for electricity — a fundamental misunderstanding of the mining process — and that the incremental supply is going to be powered by traditional energy sources like coal — which is wrong.

Supporting this point is the University of Cambridge Judge Business School’s own 2020 Global Cryptoasset Benchmarking Study , which notes that in proof of work mining “a significant majority of hashers (76%) use renewable energies as part of their energy mix.” It does, however, note that the share of renewables in miners’ total energy consumption remains at 39%.

Hydropower is listed as the number one source of energy, with 62% of surveyed hashers indicating that their mining operations are powered by hydroelectric energy. Other types of clean energies (e.g. wind and solar) rank further down, behind coal and natural gas, which respectively account for 38% and 36% of respondents’ power sources.

Despite the concerns over accurate statistical reporting, and the comparisons to other investments and industries in terms of their ESG impact, there is a clear narrative at play that Bitcoin miners are now moving towards.

Once comparison that can be drawn for the future of Bitcoin mining sustainability is the industry reaction to stringent requirements placed on cryptocurrency around anti-money laundering (AML) and ‘Know Your Customer’ (KYC) legislation.

In the latter half of the last decade there were concerns among financial regulators about the rise of Bitcoin and digital assets and their ability to be used for money laundering and even terrorist financing.

Part of the EU’s vast web of financial services legislation includes its Anti-Money Laundering Directive (AMLD), of which KYC is a significant part, and MiFiD II, which debuted in January 2018. The aim of MiFID II, is to improve record-keeping while providing better transparency on the costs of financial transactions..

Crypto custodian wallet providers and digital asset platforms were brought under the scope of AMLD4, the fourth such iteration of the law, in 2016. The European Commission’s demand was that service providers should fulfil the kind of due-diligence requirements common to other asset classes, while also putting in place measures to detect, prevent and report potential money laundering and terrorist activity. In short, AMLD4 required that financial service bodies should be able to track and trace their customers’ identity. Two years later, the fifth version of the EU law, AMLD5, bound cryptoexchanges and custodians into a more strict financial framework, compelling them to register with regulators and also to delineate how they were complying with KYC and AML guidelines.

While there was much discussion in the crypto business community about the extent to which it was possible to comply with these rules — and the fact that such requirements abut against the pseudonymous nature of cryptocurrencies — in reality no service provider would want to be ejected from the highly lucrative EU market. And so they fell in line. The regulatory requirements didn’t stop there, however.

In June 2019 the Financial Action Task Force upended cryptoasset discussions globally by debuting a series of policy recommendations for Virtual Asset Service Providers (VASPs) with a strict 12 month deadline.

Under the FATF’s ‘Travel Rule’ guidelines, financial institutions like cryptoexchanges, banks, OTC desks and wallet providers were required to share personally-identifying information about the sender and receiver of cryptocurrency transactions over $1,000. It was an effort to extend to digital and crypto transactions the same standards applicable to traditional banking transactions, typically complied with through the SWIFT messaging system.

Initially, the onerous task was considered impossible by some crypto industry participants, due to the semi-anonymous nature of cryptocurrency transactions themselves, and it caused much turmoil and stress from some quarters who hailed the ‘Travel Rule’ the end of cryptocurrency.

The German economist and policymaker Dr Marcus Pleyer took the lead role at the Financial Action Task Force on 1 July 2020, with the digital transformation of KYC and AML at the top of his two-year priority list.

But the initial punitive messaging set by reporting around the FATF’s standards had noticeably softened by the time its highly-anticipated 12 month review of Virtual Asset Service Providers appeared.

Sounding a more conciliatory tone, the report highlighted the collaborative actions that cryptoasset service providers had taken.

While the supervision of VASPs and implementation of AML/CFT obligations is generally nascent, there is evidence of progress…in particular in the development of solutions to enable the implementation of the Travel Rule...The public and private sectors have made progress in implementing the revised FATF standards.

In truth, integrating AML/KYC policies at the heart of business processes is now considered standard practice for cryptoasset service providers. As Swiss cryptobank SEBA put it at the time, crypto AML is “a complex but worthy compliance effort”.

Industry participants have shown that there is more than enough capacity for change when there is the political will and financial incentive to do so.

And the cryptoasset sector in general welcomes regulation and collaboration, as it allows institutions to enter the space in greater numbers. With the KYC/AML question at least partially solved, in September 2020 the US Conference of State Bank Supervisors unveiled a new regime for money services businesses, with 48 state regulators agreeing on a single set of supervisory rules. As Reuters reported:

The new streamlined regime applies to 78 large payment and cryptocurrency firms, which combined move over $1 trillion annually [reducing compliance costs and making] it easier for companies to operate across multiple states.

It could be argued that the same spirit of co-operation now exists in Bitcoin ESG.

In April 2021 private sector announced the Crypto Climate Accord (CCA), an industry-driven pact which mandates its signatories switch to 100% renewable energy sources by 2025, and pledge to go to net zero — to eliminate greenhouse gas emissions altogether — by 2040. It is supported by the UN’s Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Climate Champions and will debut its open-source, blockchain-based accounting standard ahead of the UN’s COP26 climate change conference scheduled for Glasgow, Scotland in November 2021.

Among the founding companies are the JP Morgan and Mastercard-backed Ethereum product builder Consensys, Ripple, enterprise blockchain builder R3 Corda, and the blockchain and cloud-computing subsidiary of EDF Energy (EPA: EDF), Exaion. The CCA’s ambition apes the kind of pledges made by the likes of BP (LSE:BP) to shrink its carbon footprint to net zero by 2050 to reduce its contribution to the climate crisis.

Adding to the CCA signatories most recently are UK-listed cryptocurrency miner Argo Blockchain (LSE: ARB), which signed up on 14 May 2021 along with North American mining pool DMG Blockchain Solutions (TSX.V: DGMI), both pledging to make reduced emissions a key part of operations going forward.

As more data continues to surface regarding Bitcoin and Bitcoin mining’s impact on the environment, it’s imperative that the industry takes real, tangible action. Peter Wall, Argo Blockchain Chief Executive

Argo Blockchain’s March 2021 move, along with DMG, to launch a green Bitcoin mining pool, is further evidence of this structural shift. Called ‘Terra Pool’, this combined computing resource will run entirely on renewable resources (mostly Canadian hydroelectric power). And as Al-Jazeera reports, Argo expanded into the United States in early 2020, with the major draw being cheap wind power near its flagship 200MW mining facility in Texas.

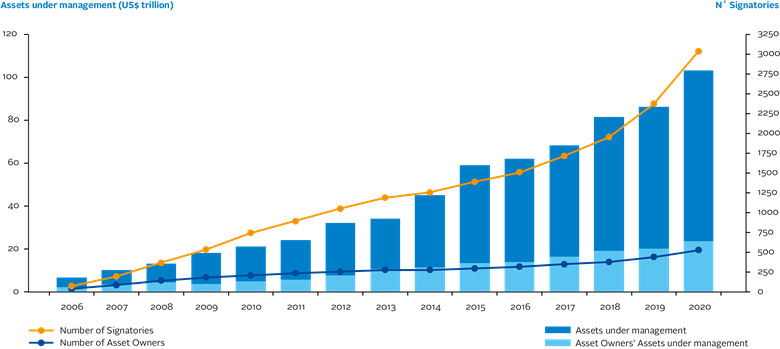

One clear target for industry groups like the CCA is to model themselves on bodies like the UN’s Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI).

While uptake was relatively slow in the 2010s, multinationals have flocked to display their green ESG credentials with PRI membership over the last five years.

PRI CEO Fiona Reynolds said in a recent op-ed in the Nikkei Asia Review:

I have little doubt that [the number of firms signing up to PRI] is set to grow exponentially over the coming years as ESG takes hold in China. And the opportunity is clearly huge.

Significant Bitcoin investors like Square (NYSE:SQ) have pledged to become carbon net zero by 2030 and suggest in their latest April 2021 Bitcoin Clean Energy Initiative whitepaper that greening bitcoin is a natural extension of its usage today.

Cleanspark ( NASDAQ:CLSK) for example, is a Utah-based software company that designs and builds microgrids. Today it claims 95% carbon-free Bitcoin mining. With a $500m market cap it is far from the largest company of its type, but its stated ambition to move to mining Bitcoin with 100% renewable energy sources is clearly the way the industry is going. Part of this is improving the efficiency of its Bitcoin mining by upgrading to the latest machines, like the Antminer S19Pro, the same strategy followed by other large Bitcoin miners like Riot Blockchain (NASDAQ:RIOT).

One other promising port of call to create a system of carbon neutral Bitcoin mining is to further expand the use of so-called ‘stranded’ energy. Modern oil extraction releases large amounts of ‘flared’ natural gas as a byproduct, and Bitcoin miners are already capitalising on these otherwise wasted resources, with some now employing prefabricated mobile datacentres on locations otherwise inaccessible to modern pipelines. As Microstrategy CEO Michael Saylor notes:

Bitcoin runs on stranded energy at the edge of the grid and acts as a global battery for otherwise idle generation facilities. It recycles wasted energy [and] provides a mechanism to commercialize clean, renewable energy wherever we may find it.

In general, in line with the Chinese curbs mentioned above, and the nation’s dramatic shift towards renewable power, industrial Bitcoin mining facilities are shifting their focus away from Asia and towards operations powered by surplus natural gas in Iceland, Norway and Canada.

Common assertions and repetitions of Bitcoin using increasing amount of energy ad infinitum are at best without merit and at worst market making for other cryptoassets.

Powerful international authorities like the OECD have recognised blockchain’s potential to aid world governments in moving financial flows to low-emission infrastructure, and Bitcoin is following.

Increasingly, ESG-focused miners are gaining market share, further greening Bitcoin’s mining landscape, and commercial priorities are clearly shifting in that direction.

Furthermore, Bitcoin advocates argue that the environmental impact of the cryptocurrency is held up to a far higher standard than any other analogous commodity or monetary system. It is certainly being held up to a much more stringent standard than gold, all the while fund managers nervous of Bitcoin’s carbon footprint pour billions into the most world’s destructive industry.

But companies in the crypto sector have long been required to fall in line with more traditional financial services industries in terms of regulation and compliance, and ESG is just the latest step along this road.

Reporting on the way that energy use is calculated must be more closely scrutinised. The vast majority of Bitcoin’s energy consumption happens during the mining process. Once coins have been issued, the energy required to validate transactions is minimal. And the suggestion that China is rapidly advancing in terms of coal-hungry mining pooling and hashrate dominance is not borne out by much of the trend analysis.

In summary, while the debate over energy and electricity use should continue, like all industries the clear goal for digital assets is to reduce their environmental impact. The data shows that Bitcoin poses little threat to investing with an ethical, environmental and sustainable concern at heart and the two priorities are far from mutually exclusive.

AVVISO IMPORTANTE:

Questo articolo non costituisce consulenza finanziaria, né rappresenta un'offerta o un invito all'acquisto di prodotti finanziari. Questo articolo è solo a scopo informativo generale, e non vi è alcuna assicurazione o garanzia esplicita o implicita sulla correttezza, accuratezza, completezza o correttezza di questo articolo o delle opinioni in esso contenute. Si consiglia di non fare affidamento sulla correttezza, accuratezza, completezza o correttezza di questo articolo o delle opinioni in esso contenute. Si prega di notare che questo articolo non costituisce né consulenza finanziaria né un'offerta o un invito all'acquisizione di prodotti finanziari o criptovalute.

PRIMA DI INVESTIRE IN CRYPTO ETP, GLI INVESTITORI POTENZIALI DOVREBBERO CONSIDERARE QUANTO SEGUE:

Gli investitori potenziali dovrebbero cercare consulenza indipendente e prendere in considerazione le informazioni rilevanti contenute nel prospetto base e nelle condizioni finali degli ETP, in particolare i fattori di rischio menzionati in essi. Il capitale investito è a rischio, e le perdite fino all'importo investito sono possibili. Il prodotto è soggetto a un rischio controparte intrinseco nei confronti dell'emittente degli ETP e può subire perdite fino a una perdita totale se l'emittente non adempie ai suoi obblighi contrattuali. La struttura legale degli ETP è equivalente a quella di un titolo di debito. Gli ETP sono trattati come altri strumenti finanziari.

L'ETC Group è nata da una chiara missione: fornire agli investitori l'accesso al vasto potenziale di crescita nell'ambito delle criptovalute e degli asset digitali. Il nostro track record comprovato ci rende un partner affidabile: in oltre tre anni di successi, abbiamo consolidato la nostra posizione come emittenti di cripto-titoli con sede in Germania e siamo diventati un punto di riferimento europeo per soluzioni d'investimento in questo dinamico settore.

Con un solido track record di oltre tre anni, crediamo che sfruttando l'esperienza e le conoscenze del settore finanziario tradizionale e applicandole a questa nuova ed entusiasmante classe di asset, possiamo portare sul mercato prodotti d'investimento di prim'ordine.

Nel giugno del 2020, ETC Group ha lanciato il primo ETP su Bitcoin con compensazione centralizzata al mondo, quotato su Deutsche Börse XETRA, la più grande borsa di ETF in Europa. Da allora, la società è stata un pioniere dei prodotti negoziati in borsa basati sulle valute digitali con numerose idee di prodotto innovative. ETC Group è costantemente impegnata ad ampliare la propria gamma di ETP di qualità istituzionale sulle criptovalute, offrendo agli investitori la possibilità di investire in Bitcoin, Ethereum, Cardano, Solana e altri asset digitali popolari sulle principali borse europee.